Leon Josephson

Leon Josephson | |

|---|---|

| Born | June 17, 1898 |

| Died | February 1966 (aged 68) |

| Nationality | American |

| Spouse | Lucy Ellen (Wishart) |

| Espionage activity | |

| Codename | Bernard A. Hirshfield |

| Family | Barney Josephson (brother) |

Leon Josephson (June 17, 1898 – February 1966) was an American Communist labor lawyer for International Labor Defense and a Soviet spy. He received a 1947 Contempt of Congress citation from House Un-American Activities Committee.[3][4][5][6]

Background

[edit]Leon Josephson was born into a Jewish family in 1898, in either Goldingen[1] or Libau[2] in Latvia, Russian Empire. He had four elder siblings: Ethel, David, Louis, and Lillie. His family emigrated from Libau in 1900 and settled in Trenton, New Jersey, where another brother, Barney, was born in 1902. His father, Joseph, a cobbler, died shortly after Barney's birth. His mother, Bertha Hirschfield, was a seamstress. Leon attended Trenton High School and graduated from New York University Law School in 1919.[3][4][5][6]

Career

[edit]Josephson and his brother Louis became lawyers. In 1921, Josephson was admitted to the New Jersey state bar. In 1923, he traveled to the Soviet Union. In 1927, he visited Berlin. He practiced law in Trenton from 1926 to 1934.[4][5][6]

In 1926, Josephson joined the Communist Party (then the Workers Party of America).[6][7]

International Labor Defense

[edit]

In 1929, Josephson was a lawyer for International Labor Defense (ILD). In 1929, he served on the defense team (along with Arthur Garfield Hays of the Sacco and Vanzetti case and Dr. John Randolph Neal of the Scopes Trial) for union organizers in Loray Mill strike in Gastonia, North Carolina charged with conspiracy in the strike-related killing of a police chief. Co-defendant Fred Beal was later to charge that Josephson's defense strategy of sticking to the facts (a sequence of events in which strikers were attacked and a labor protester was shot and killed) and of not playing into the prosecution's attempt to place the defendants' communist beliefs on trial was deliberately sabotaged by the party intent on creating further martyrs.[8]

Josephson traveled to Europe for ILD in 1929, 1930, and 1931. In 1932, he traveled to the Soviet Union.[3][6][7][9][10][11][12] Beal, then in Soviet exile, in later testimony to House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC, 1947) claimed that he had met Josephson several times in Moscow and that he knew him to be an "GPU agent".[13][14] At the time, in 1932, Josephson was formally registered as an employee of the Soviet trading agency Amtorg.[6][7]

Espionage

[edit]At some point, Josephson had begun working for the Soviet secret services. One of his codenames or covers was "Bernard A. Hirschfield."[15][16] In 1932, he was "involved in providing support for the Russian illegal (either Comintern or Military Intelligence) LYND, then visiting India."[15]

On August 31, 1934 (according to the 1947 HUAC report – see below), Josephson signed his name "Bernard A. Hirschfield," witnessed by Harry Kwiet (with whom he had associated in 1929 during the Gastonia trial), on a passport application for one "Samuel Liptzen" with a photo of Gerhart Eisler (identified in 1946 by former Communist and Daily Worker editor Louis F. Budenz as a "mastermind" Soviet spy).[6]

By 1935, Josephson was reporting to Alexander Ulanovsky, recently rezident or Soviet station chief in New York and whose network members included Whittaker Chambers). Ulanovsky had resurfaced in Copenhagen to head Soviet espionage ring that collected military information on Nazi Germany. The Danish police arrested Ulanovsky and two Americans, Leon Josephson and George Mink, following a search of their hotel room which turned up codes, money, and multiple passports.[6][17] The motive for the search was a charge of rape against Mink by a chambermaid. Ulanovsky claimed they were Jewish anti-fascists acting on their own, but the police produced information, possibly obtained from the Gestapo, that proved they were working for Soviet intelligence. The Danes held a secret trial and convicted Ulanovsky of spying and sentenced him to eighteen months in prison. He was later deported to the Soviet Union. Josephson returned to America.[citation needed] Mink had four fake passports on him. Danish investigators got help from American counterparts, who learned that Mink's passport for "Harry Kaplan" had been stolen by Leon Josephson's brother, Barney Josephson. Josephson spent four months in jail, awaiting trial. A Danish court found the evidence insufficient, and Josephson returned to the States. Later, State Department handwriting experts determined that the signature for another of the four passports ("Al Gottlieb") was Josephson's.[7] A third American with them was "Nicholas Sherman," really Robert Gordon Switz (previously arrested in Paris in 1933 in what Chambers later called the "Switz Affair"[6][18]).[7][19][20]

Around 1938, Josephson helped steal the papers of communist defector Jay Lovestone, according to Lovestone himself during testimony to the Dies Committee.[17]

Café Society

[edit]

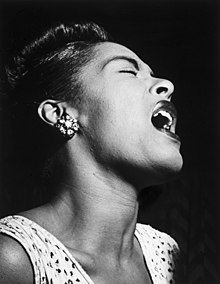

In December 1938, Leon borrowed $6,000 so his brother Barney could open Café Society in a basement room on Sheridan Square, West Village, New York City.[3][4] Billie Holiday sang in Café Society's opening show in 1938 and performed there for the next nine months. Josephson set down certain rules around the performance of "Strange Fruit" at the club: it would close Holiday's set; the waiters would stop serving just before it; the room would be in darkness except for a spotlight on Holiday's face; and there would be no encore.[4][5]

Barney Josephson later said:

I wanted a club where blacks and whites worked together behind the footlights and sat together out front ... There wasn't, so far as I know, a place like it in New York or in the whole country.[4]

Few nightclubs permitted blacks and whites to mix in the audience. The Cotton Club in Harlem was segregated, admitting only occasional black celebrities to sit at obscure tables and limiting black customers to the back of the room behind the pillars and partitions. Clubs south of Harlem, like the Kit Kat Club, did not let African Americans in at all. Segregation in the States was relentless: as Josephson told Reuters in 1984, "The only way they'd let Duke Ellington's mother in was if she was playing in the band."[4][5]

HUAC

[edit]HUAC 1: no-show

[edit]

On February 2, 1947, Josephson failed to appear under subpoena. He would have appeared with Gerhart Eisler, Ruth Fischer (Eisler's sister), Wiliam Nowell, Louis F. Budenz, and others. On that date, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) produced evidence that Josephson had forged his name as "Bernard A. Hirshfield" for a "Samuel Liptzen" on a passport application dated August 31, 1934, which bore a photo of Gerhart Eisler. On February 5, Josephson sent a telegram to HUAC chairman U.S. Rep. J. Parnell Thomas that advised, "Unable appear before your committee February 6th, due inadequate notice of less than 48 hours. Counsel advises me such short notice unreasonable and that I am entitled to reasonable notice. Willing appear at later date fixed by you if reasonable notice given me."[6]

Nixon's maiden speech to Congress

[edit]

On February 18, 1947, freshman U.S. Representative Richard M. Nixon mentioned Josephson's name often in his maiden speech to Congress:

Mr. Speaker, on February 6, when the Committee on Un-American Activities opened its session at 10 o'clock, it had by previous investigation, tied together the loose end of one chapter of a foreign-directed conspiracy whose aim and purpose was to undermine and destroy the government of the United States. The principal character of this conspiracy was Gerbert Eisler, alias Berger, alias Brown, alias Gerhart, alias Edwards, alias Liptzin, alias Eisman, a seasoned agent of the Communist International ...

Two other conspirators and comrades of Eisler, Leon Josephson and Samuel Liptzin, who were subpenaed to appear, did not appear; Josephson contended by telegram that two days was not sufficient notice for him to come from New York to Washington ... It is no wonder that Eisler refused to talk and Josephson and Liptzin did not respond to the subpenaes ...

I think I am safe I announcing to the House that the committee will deal with Mr. Josephson and Mr. Liptzin at a very early date ... Now the handwriting on this application, according to the questioned documents experts of the Treasury Department, is that of Leo Josephson; the name on this application is that of Samuel Liptzin the picture on this application is that of Gerhart Eisler; the signature of the identifying witness, Bernard A. Hirschfield, is also in the handwriting of Leon Josephson ...[16]

HUAC 2: contempt of Congress

[edit]On March 5, 1947, several witnesses appeared before HUAC. First came the real Samuel Liptzen, accompanied by labor lawyer Edward Kuntz as counsel: both were sworn in. Liptzen was born on March 13, 1893, in Lipsk, Russia (now Liepinė, Lithuania). In April 1909. he emigrated to the United States. On March 13, 1917, he became an American citizen. In 1920 or 1921, Liptzen became a Party member. He had been a tailor and a member of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America. Then he worked in the fur industry until he became sick from dye. Between 1926 and 1928, he traveled twice to Canada (and again in the summer of 1945). In 1928 or 1929, he ran for the New York City Assembly. In 1935, he lived in Los Angeles (while ill). For two or three years, he had worked in the offices of the Morning Freiheit (Morgen Freiheit, a Yiddish language newspaper affiliated with the Communist Party USA and with offices in the same building as the Daily Worker, founded by Moissaye Olgin in 1922). (Liptzen called it a "left-wing" and "progressive" newspaper.) He claimed he had been unable to appear on February 6, 1947, as required by subpoena because of the illness of "the missus with whom I have the rooms," named Mrs. Annie Halland (Holland). He also stated that he had never applied for a passport – despite a passport application in his name dated August 31, 1934. Liptzen swore on the spot: "It isn't my signature ... absolutely not," nor his photo, nor a photo of anyone he knew. Liptzen could not produce his naturalization papers, nor when he lost them due to robbery, nor exactly where he lived when his home was robbed. Liptzen also denied ever "loaning" anyone his naturalization papers or knowing Josephson or Eisler (including any of his aliases or codenames).[6]

Attorney Edward Kuntz was representing both Liptzen and the Morning Freiheit; until a few years before, he had already represented the Daily Worker. Kuntz described building occupants at 35 East 12th Street in New York City: CPUSA national committee on top ninth floor, Daily Worker editorial offices on eighth, F. & D. Printing Co. on seventh, Morning Freiheit sixth, CPUSA state on fifth, Daily Worker business offices on second, and F. & D. Printing Co. presses in the basement. Kuntz explained that he had changed the legal status of the Freiheit from business to membership corporation and that there were some communists who were corporate members and contributing journalists.

Nixon resumed questioning of Liptzen thereafter, asking him how he had managed not to see Eisler in that building; Liptzen simply denied knowing him or having seen him. HUAC member U.S. Rep. Bonner resumed questioning of Kuntz to ask him more about the Freiheit and the owners of the building and corporation therein. Kuntz could tell him little other than the current head of the Freiheit: "Lechovitzky." HUAC member U.S. Rep. Vail resume questioning of Liptzen regarding his alleged telegram to decline appearance. Liptzen confirmed that he wrote humorous pieces for the Freiheit and had written the book In Spite of Tears. (Vail exclaimed, "You arrived at the age of 17 and you still write in Jewish (Yiddish)?" Vail and Stripling resumed questioning of Kuntz, who admitted that for some years up to the early 1940s he had headed the staff of International Labor Defense (which had a peak of 250–300 volunteer labor lawyers) and was chairman of the legal committee when ILD dissolved but denied knowing Josephson there. (In 1946 the ILD merged with the National Federation for Constitutional Liberties or NFCL and National Negro Congress or NNC to form the Civil Rights Congress or CRC).) When asked by Stripling whether he was sympathetic to communism, Kuntz answered, "Most of it" but denied being a communist. Kuntz, who denied knowing Eisler but admitted he knew Josephson because "I used to be a habitue of Cafe Society." Their joint testimony ended with HUAC's informing Liptzen that he remained under subpoena and was "not excused" but rather subject to recall. (Stripling managed to work in mention that U.S. Rep. Vito Marcantonio was ILD president.)[6][21][22]

That day, Josephson also appeared under subpoena before HUAC. He refused to be sworn in due to the "unconstitutionality of this committee" and refused to answer questions. Samuel A. Newburger of New York City served as his legal counsel.[6][23]

The hearing's transcript records:

The Chairman: Mr. Josephson, will you stand and be sworn?

Mr. Josephson: I will not be sworn.

Mr. Stripling: Will you stand?

Mr. Josephson: I will stand.

(Mr. Josephson stands.)

Mr. Stripling: Do you refuse to be sworn?

Mr. Josephson: I refuse to be sworn.

Mr. Stripling: You refuse to give testimony before this sub-committee?

Mr. Josephson: Until I have had an opportunity to determine through the courts the legality of this committee.

The Chairman: You refuse to be sworn, and you refuse to give testimony before this committee at this hearing today?

Mr. Josephson: Yes.

The appellant was then excused subject to call either by the sub-committee or the full committee.[23]

As a result, Josephson was found guilty of contempt of Congress.[23]

HUAC 3: evidence

[edit]

On March 21, 1947, HUAC held further hearings with witnesses about Eisler and Josephson.

HUAC investigator (and former FBI agent) Louis J. Russell provided an overview of his life, from birth in Latvia, espionage in the States and Denmark with George Mink during the 1930s, and efforts to make the false application for Gerhart Eisler's passport in 1934. Russell noted that penniless brother Barney Josephson had made trips to Europe in the mid-1930s before opening Café Society in 1938. He also observed that in 1946 Barney was a sponsor of "Spanish Refugee Appeal," a branch of the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee (which had paid Eisler funds in 1941 under another false name). Russell then presented 1938 Dies Committee testimony from John P. Frey, former president of the metal trades department of the AFL that claimed that Mink had been involved in the Soviet assassination of Leon Trotsky and proceeded to insert four pages of transcripts into the record that included 1938 testimony by Earl Browder, Benjamin Gitlow, and Jay Lovestone among others, all about Mink. Russell documented Josephson's Party membership and loyalty to the Soviet Union with quotes from his own writings, e.g., "The new Soviet constitution and electoral law are the most democratic in the world" and his dream of a "Soviet America." HUAC chief investigator Robert E. Stripling concluded "Mr. Eisler and Mr. Josephson ... are in the higher echelons of the Communist International." Russell then showed Josephson's connection to two current Federal employees, Sol Rabkin and Milton Fischer, both of whom had affiliations with known "communist fronts" including the National Lawyers Guild (Rabkin). Stripling complained that Martin Popper had called as Josephson's lawyer to ask for extension on appearance in the subpoena, only to later deny he was representing Josephson. (Stripling observed that Popper was long-time executive secretary of the National Lawyers Guild.) Russell then proceeded to provide his report on the real Samual Liptzen. Liptzen had failed to report trips to Mexico and Canada to the FBI. He had failed to report the robbery of his naturalization papers for two years. Finally, Russell found an article in the Jewish Daily Forward (Yiddish Forverts) dated March 8, 1947, that stated that Liptzen and Josephson are friends and that Liptzen had a long history in the Soviet underground, for which he was expelled from unions and wound up at the Freiheit.[6][24]

Alwyn Cole, Treasury examiner, reported that his examination of handwriting on the 1934 passport application revealed that the handwriting of the signature "Bernard A. Hirschfield" belonged to Leon Josephson. Cole did not find the signature "Samuel Liptzen" as confidently belonging to Gerhart Eisler, though he was confident that the real Samuel Liptzen had not signed.[6]

Fred Erwin Beal, indicted during the Loray Mill strike of 1929, testified next. Josephson (with Clarence Miller of the National Textile Workers Union and Juliet Stuart Poyntz of the International Labor Defense) had helped arrange false passports for many of those indicted, including himself, and helped them flee to the Soviet Union. Beal saw Josephson in Moscow several times and knew him to be a GPU agent. After some years, Beal returned to the States, although he faced possible re-arrest and imprisonment, rather than stay in the USSR. Josephson, William Z. Foster, and other high-level communists persuaded Beal to return to Moscow. He saw George Mink there several times. Again he left: in 1940, he was serving four years in the Raleigh Penitentiary, where the FBI visited him several times.[6]

Columnists like Dorothy Kilgallen, Lee Mortimer, Westbrook Pegler, and Walter Winchell attacked. Within weeks of these attacks, business at Café Society fell away, and his brother Barney had to sell.[4][5]

HUAC 4: evidence

[edit]On October 28, 1953, Josephson with attorney Samuel Neuberger again appeared under subpoena before HUAC. He told the Committee that he was working with his brother "Warren Josephson" in his brother's restaurant, rather than state Barney Josephson and Cafe Society. Josephson confirmed that he had worked in fact at both uptown and downtown branches of Cafe Society. He refused to confirm whether he had associated in the mid-1930s with George Mink or whether he had traveled with Mink to Copenhagen, or whether Danish police had arrested them there as Soviet spies. Louise Bransten with attorney Joseph Forer immediately followed him on the stand.[25]

Espionage: Rosenberg Case

[edit]

According to the 2007 book Spies, Josephson and John L. Spivak "burglarized" the offices of labor lawyer O. John Rogge, attorney for David Greenglass, and stole papers later published by the Communist Party to discredit Greenglass in his testimony in the Rosenberg Case.[17][26]

Later life

[edit]From 1952 to 1956, Josephson taught Soviet Law at the Jefferson School of Social Science.[27]

Personal life and death

[edit]Josephson married Lucy Wishart in 1945; they had two children.[3][6] Josephson died in February 1966 of a "massive heart attack."[3]

Works

[edit]Shortly after his HUAC testimony, Josephson publicly avowed membership in the Communist Party USA in the influential leftist journal, the New Masses.

- "The New Soviet Electoral Law," The Communist (1937)[24]

- "I Am A Communist," New Masses (1947)[28]

- The Individual in Soviet Law (1957)[27]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b U.S., Passport Applications, 1795-1925

- ^ a b New Jersey, Naturalization Records, 1878–1945

- ^ a b c d e f Josephson, Barney; Trilling-Josephson, Terry (2009). Cafe Society: The Wrong Place for the Right People. University of Illinois Press. pp. 10–11 (Cafe Society), 78–90 (family), 99 (Gastonia), 106 (loan), 224–225 (arrest, wife, kids), 226 (death). ISBN 9780252095832. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wilson, John S. (30 September 1988). "Barney Josephson, Owner of Cafe Society Jazz Club, Is Dead at 86". New York Times. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Folkart, Burt A. (1 October 1988). "Barney Josephson: Led Nightclub Integration". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Investigation of un-American propaganda activities in the United States. (regarding Leon Josephson and Samuel Liptzen) by the United States Congress House Committee on Un-American Activities". U.S. Government Printing Office. 1947. pp. 1–4 (Samuel Liptzen), 4 (Edward Kuntz), 4–12 (Liptzen), 12–13 (Kuntz), 13–14 (Liptzen), 14–16 (Kuntz), 16–19 (Liptzen), 19–20 (Stephen W. Birmingham), 20–22 (Liptzen), 22–23 (Kuntz), 23–24 (Liptzen), 24–25 (Kuntz), 25–28 (Leon Josephson), 29–32 (HUAC record), 32–50 (Russell HUAC bio), 34–35 (Eislier passport), 35 (wife Lucy), 36–39 (Copenhagen), 39 (Frey), 50–54 (Alwyn Cole), 54–69 (Fred Erwin Beal), 69–XXX (Liston M. Oak). Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Haynes, John Earl; Klehr, Harvey (2000). Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America. Yale University Press. pp. 80–81. ISBN 0300084625. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ HOWIE, SAM (1996). "Review of Gastonia 1929: The Story of the Loray Mill Strike". Appalachian Journal. 23 (3): (326–331) 329. ISSN 0090-3779. JSTOR 40933777.

- ^ "Amy Schechter, Daughter of Dr. Solomon Schechter, Held for Murder in Strike". Jewish Telegraph Agency. 23 July 1929. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ Salmond, John A. (1995). Gastonia 1929: The Story of the Loray Mill Strike. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 200 (fn 16). ISBN 9780807822371.

- ^ Pope, Liston (1942). Millhands & Preachers: A Study of Gastonia, Volume 15. Yale University Press. p. 287. ISBN 0300001827. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ Irving, Bernstein (2010). The Lean Years: A History of the American Worker, 1920–1933. Haymarket Books. p. 25. ISBN 9781608460632. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ "Investigation of un-American propaganda activities in the United States. (regarding Leon Josephson and Samuel Liptzen) by the United States Congress House Committee on Un-American Activities". U.S. Government Printing Office. 1947. pp. 54–69 (Fred Erwin Beal). Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ Haynes, John Earl; Klehr, Harvey (2000-01-01). Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America. Yale University Press. pp. 80–81, 159, 174. ISBN 978-0-300-12987-8.

- ^ a b "Leon JOSEPHSON (1) / Barney JOSEPHSON (2), alias (1) Bernard A HIRSCHFIELD: Latvian". National Archives. 30 March 2004. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ a b "Congressman Nixon's Maiden Speech To The House Of Representatives". Watergate. 18 February 1947. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ a b c Romerstein, Herbert; Breindel, Eric (1 October 2001). The Venona Secrets: Exposing Soviet Espionage and America's Traitors. Regnery. pp. 107 (Underground), 109 (CPUSA), 110–113 (Lovestone), 123 (Copenhagen), 252 (Rogge, Greenglass, Rosenbergs). ISBN 9781596987326. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ^ Chambers, Whittaker (May 1952). Witness. New York: Random House. pp. 50–51. ISBN 9780895269157. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ Volodarsky, Boris (2015). Stalin's Agent: The Life and Death of Alexander Orlov. Oxford University Press. pp. 95–96. ISBN 9780199656585. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ^ Haynes, John Earl (18 February 2009). American Communism and Anticommunism: A Historian's Bibliography and Guide to the Literature. John Earl Haynes: Historical Writings. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ^ Liptsin, Sem (1946). Ber Green [pseud.] (ed.). In Spite of Tears. Translated by S. P. Rudens. Amcho Publishers. LCCN 46023086.

- ^ There are 18 entries for "Sem Liptzin" in the Library of Congress as of January 13, 2018.

- ^ a b c "United States v. Josephson, 165 F.2d 82 (2d Cir. 1947)". Justia US Law. 9 December 1947. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ a b Josephson, Leon (October 1937). "The New Soviet Electoral Law". The Communist.

- ^ Interlocking Subversion in Government Departments. US GPO. 1953. pp. 1032–1033. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ^ Klehr, Harvey; Haynes, John Earl; Vassiliev, Alexander (2009). Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. pp. 164. ISBN 9780300155723. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ^ a b Josephson, Leon (September 1957). The Individual in Soviet Law. New Century Publishers. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ Josephson, Leon (1 April 1947). "I Am A Communist". New Masses.

External links

[edit]- "Leon JOSEPHSON (1) / Barney JOSEPHSON (2), alias (1) Bernard A HIRSCHFIELD: Latvian". National Archives. 30 March 2004. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- University of Massachusetts Library (Credo): Civil Rights Congress (U.S.) – United States of America v. Leon Josephson dissenting opinion press release (December 12, 1947)

- 1898 births

- 1966 deaths

- American trade union leaders

- 20th-century American lawyers

- American political activists

- Members of the Communist Party USA

- Lawyers from New York City

- Prisoners and detainees of the United States federal government

- American spies for the Soviet Union

- Espionage in the United States

- American communists